Sociological research

The art community lacks a bilingual online magazine. A sense of peripherality

Zuzana Révészová

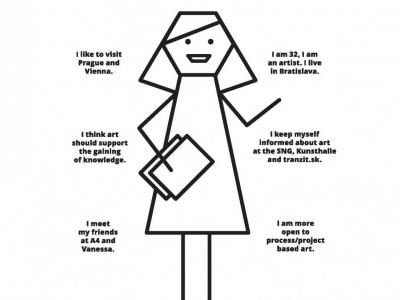

Who I am and what I say

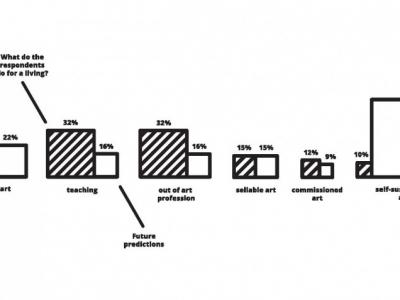

A periphery that has potential. That’s how the atmosphere of the Bratislava art milieu is perceived by the respondents of the mini survey which we conducted as part of the preparation for the Small/Big World exhibition at tranzit.sk. Our research was intended to determine quantitatively the nature of the Bratislava art community, its configuration, preferences and opinions – and to become part of the exhibition in the form of infographics.

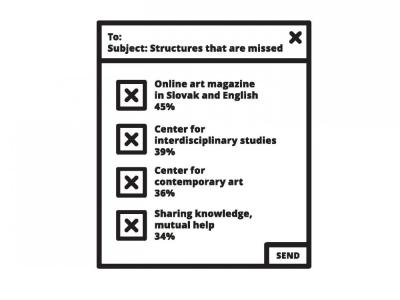

Resulting from further indicators which we discovered thanks to the surveys, there may be some reasons for gloomier feelings about the peripherality of the art scene. Our respondents are conscious of deficiencies in the institutional background of the art milieu, especially the absence of a high-quality online bilingual cultural journal (in Slovak and English), and of an institution for the support of interdisciplinary studies. The milieu around tranzit.sk, from which most of the respondents come, gives preference to research-based art tendencies. The aim of this art is to enrich the viewer with knowledge and/or to exert pressure for social change.

Briefly on methods

We conducted the survey online using a questionnaire portal and inserted it in the tranzit.sk Facebook pages. At the same time, we sent targeted emails to certain artists and tranzit.sk sympathisers. It is important to keep in mind that the answers do not characterise the entire art community in Bratislava but rather a select group within it, moving around institutions such as tranzit.sk. We received 74 replies. Considering the very small sample, it is not possible to generalise. Nonetheless, we believe that it has a certain testimonial value. If at least 30 people (less than 50 % of our sample) in the Bratislava environment (and furthermore, in the specifically artistic world) think something, that is a relevant statement in our opinion. A majority of respondents in this survey were women (60 %) and in the art field identified in the role of artists (almost 50 %) and living in Bratislava (60 %).

I and my surroundings.

In an attempt to discover the profile of our respondents’ circles of friends and social groups, we asked for an age and gender breakdown of their friends, and also their native language and geographical origin. In this enquiry we were interested mainly in homogeneity or heterogeneity in the aspects re-searched. For a majority of respondents, they were predominantly surrounded by a group of friends whose ages ranged from 20 to 30. The respondents themselves were most often in this group (average age 31 years, median 32). It was not the case, however, that there were strikingly fewer acquaintances or friends of other age groups. One can therefore summarise by saying that a certain form of intergenerational exchange may exist in the Bratislava milieu.

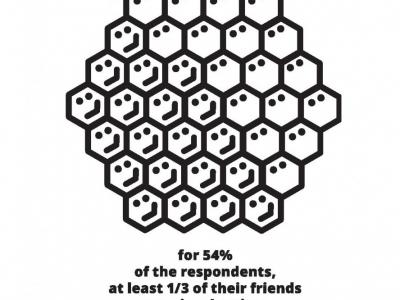

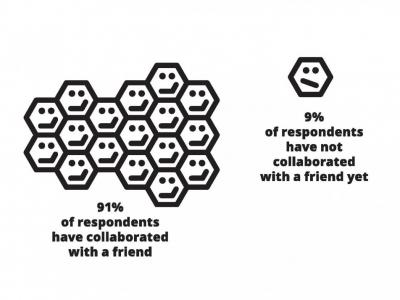

More than half of the respondents stated that at least one-third of their friends or acquaintances are artists, though only a smaller number of these are involved in the sphere of visual art. Almost 84 % of those responding had at some time in their lives collaborated on an art project with a friend, which means that artists often involved friends who were not professional artists in their projects. At the same time, however, that pointed to a very intensive connection process forming strong bonds in creative art.

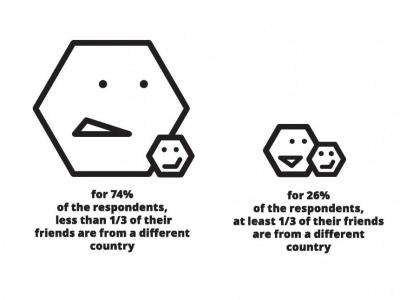

In terms of gender diffusion, the overwhelming majority of respondents reported very great heterogeneity, while showing considerable homogeneity in terms of geographical origin. It appears that almost all of those asked had friends exclusively of Slovak origin and friends of the same native language, though coming from different places and communities within Slovakia. The Bratislava art community hence may be quite enclosed in the Slovak linguistic milieu. Even if in other parts of the text there is evidence of regular contact with foreign lands, close relationships indicate a relatively considerable non-communicativeness towards foreigners.

Where am I going? What/who am I following?

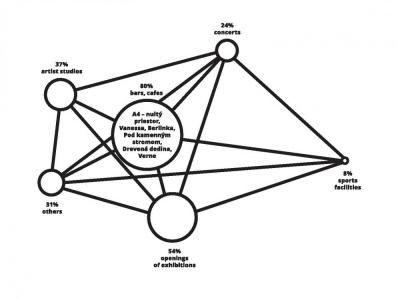

It will scarcely be surprising that one finds this (relatively young) group of respondents mainly meeting their friends and acquaintances in cafés and bars. Other popular choices for where respondents liked best to meet friends were artists’ studios and galleries during exhibition openings. A fact that may be surprising is that rather than the current new trendy cafés of “the third Berlin generation” they tend to prefer the spaces of the Vanessa bistro or Drevená dedina. A kind of centre for this group is, probably, the A4, with the largest number of fans. Also popular is café Berlínka in the Slovak National Gallery. The SNG is the most visited institution for respondents who want information about what is currently happening. Also showing strongly is the almost equally popular Dom umenia/Kunsthalle Bratislava and the tranzit.sk.

On the other hand, respondents show a very great diversity on the question of which individual public figures they admire, or are inspired by, in art or non-art life in Bratislava, Slovakia or the world. Only a few names were repeated – for example, that of Alexandra Kusá, which is probably connected with the high attendance figures of the Slovak National Gallery as a place for acquiring information. Another often-mentioned individual was Ilona Németh, who is a teacher at the Academy of Fine Art and Design. Though this cannot be determined with certainty, she may have been inspiring for that part of the respondents who were her students. A similar diversity is shown regarding the question of which artistic grouping respondents felt themselves part of. One of these groups seems to be the Academy of Fine Art and Design itself. The school is an institution which by its nature has art groups from a given studio or year clustering round it. Another relatively frequently mentioned institution was Ku.Ba, the Kultúrna Bratislava association – which is probably connected with the popularity of the spaces and activities of A4. There is no indication, however, of unambiguous support for a certain group. A number of artistic groupings were mentioned which have a small number of artist-members.

It appears that a notable element binding the art community in Bratislava is its relationship to neighbouring artistic spheres. The greater number of respondents regularly go to Vienna, Prague and Brno for inspiration and also follow the scenes there from a distance. The respondents visit many institutions in these cities (MUMOK, MQ, Galerie Rudolfinum, DOX, tranzitdisplay, The Brno House of Arts, Forum for Architecture and Media in café Prague in Brno). Surprisingly, Budapest, despite its geographical closeness, is not so interesting for the art community. Other sig-nificant places are Berlin, Venice (at the Biennale), London and Paris. Some people mentioned Tbilisi and the Georgian art scene. The inspiring individuals in European and world art were again greatly diverse: the only name that occurred twice was Marina Abramović.

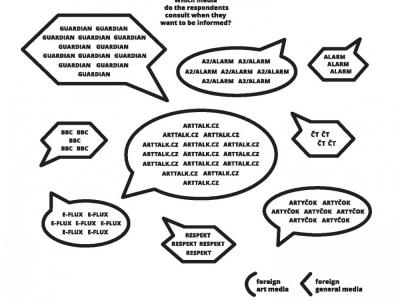

There was a very interesting agreement on the question of media sources, which (as in the preceding categories in this article) we ascertained by open questions. Of foreign media (the question encompassed online media and print newspapers, radio and TV for general information) the most-followed source is The Guardian, followed by the BBC and Czech Television. The British information sources favoured for foreign reports were replaced by Czech media in particular when the question was which foreign media offered information on art activities. The most commonly-used source is artalk.cz, followed by the New York e-flux, the Czech magazines A2/Alarm and artyčok.tv.

The most frequently used Slovak media were

FlashArt, followed by Advojka/Alarm, the magazíne Profil, also artalk.cz and the cultural sections of the daily newspapers Denník N and SME, and Radio FM. FlashArt does not actually have a purely Slovak edition: media coverage of the art sphere therefore depends on the existence of shared Czechoslovak coverage. FlashArt and also the Slovak Profil are print media, and in reply to the question, “What type of community space in Bratislava do you find most lacking?” as many as 45% said that it was an online contemporary art magazine in Slovak and English. In terms of general news reports the respondents follow the daily newspapers Denník N and SME, with the next most popular being the statutory public media.

Art and I

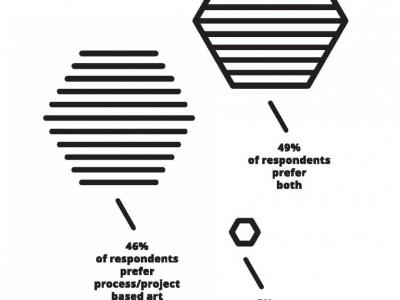

Of the other types of art/community spaces which respondents judged to be lacking in Bratislava, the most emphasised were a centre of interdisciplinary studies (almost 40 %) and a centre for contemporary art (36.5 %). Connected probably with this is the type of art which respondents prefer. In response to the question whether they prefer object-based art, process-based art, or both, more than 40 % opted for both and almost 38 % identified with process-based art. Only something over 4 % stated a preference for object-based art.

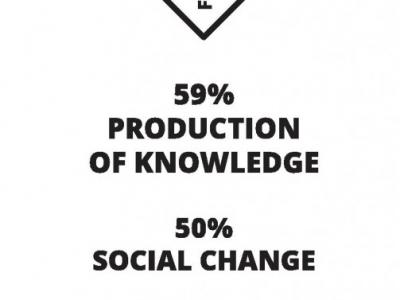

We learned what the function of art is, according to respondents. Art is perceived as a means for the production of knowledge (almost 60 % of respondents). Half of the respondents think that art is also an instrument of social change. The third most emphatic description was as an instrument of emancipation (over 43 %). Art is considered a means to an aesthetic experience by something over 40 %. This evaluation corresponds to the preceding assumptions and also to the specific group created by the public of tranzit.sk, since it is about a space for contemporary art in which there is support for research-based art, which to a great extent overlaps into other disciplines and social activity.

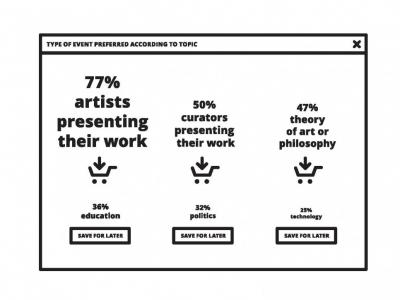

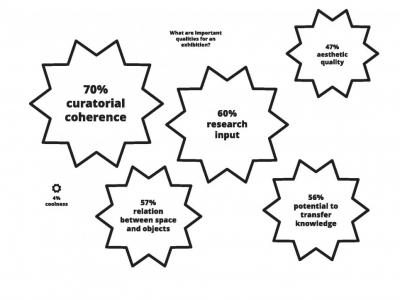

The evaluation of the quality of an exhibition was in a similar spirit. The most important attributes of a high-quality exhibition seemed to be curatorial coherence (70 % agreement), research contribution (61 %) and the relationship between the space and the art displayed (57 %). The respondents gave very little importance to the issue of whether the exhibition was “cool” (4 %). Aesthetic quality is important for less than 50 % of respondents. As regards the forms of events which respondents prefer, these are particularly actions in which the artists present their work (77 %). Curatorial presentations came in second place; the difference in popularity between first and second place, however, was almost 30 %. Immediately after the curatorial presentations came presentations from the theory of art, global problems, and philosophy.

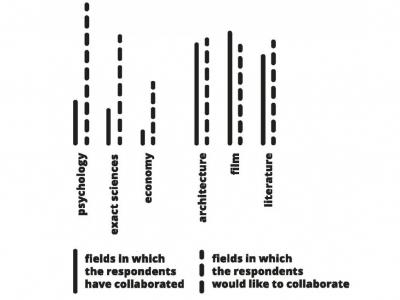

We also asked about areas in which respondents had already actively collaborated and those which they would like to get more involved in. Most frequently, respondents had already collaborated in film (over 50 %), architecture (45 %) and literature (41 %). On the question of which field they would like to collaborate in, surprisingly the most popular was psychology (37 %), followed by anthropology (33 %) and exact sciences (27 %). In these results one can see an openness to interdisciplinary collaborations which is very characteristic, for example, of the activity of tranzit.sk.

I in Bratislava, Bratislava in me

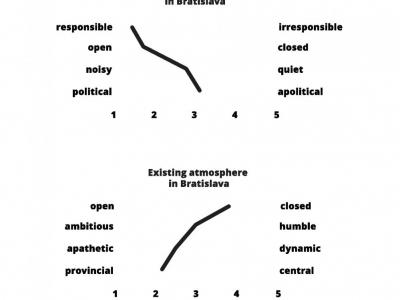

In evaluating the moods of the Bratislava art community, we wanted to delineate the situation as precisely as possible by a quantitative form of research. The method we chose (semantic differential) offers a positioning of collective moods on scales of conceptual opposites. Hence, when asked what kind of atmosphere there is in the Bratislava community, respondents could choose between pair-options: full of potential – without potential, provincial – central, apathetic – dynamic, conflicting - peaceful, grey – colourful, open – closed, ambitious – humble, vital – dead, young – old. Most of these categories were assigned values somewhere in the middle. An exception was the “provincial” category, to which respondents came much closer than to the “central” category. There was a further inclination towards the category “closed”(as opposed to “open”). Other mild leanings were recorded towards the categories “full of potential”, “apathetic” and “young”.

We used an equivalent method in evaluating ideas on the ideal community. We employed pairings: responsible – irresponsible, visible – invisible, political – apolitical, breaking norms – following norms, saving – consuming, philanthropic – profit-orientated, noisy – quiet, open – closed, sharing – individualistic. At first glance, it was clear to us that here there was a much greater tilt towards positive values than in the first instance. The political – apolitical pairing sustained neutral values, but respondents showed an emphatic preference for the “responsible” category. A striking inclination could also be seen in the categories “saving” and “open” (which simply underlines the contrast between how reality is perceived and the ideal). We also detected a mild inclination toward the categories “breaking norms”, “philanthropic”, “sharing”, and “visible”. We did not register any inclination towards negative categories.

Conclusion: Institutional support in future growth

If we were to summarise the desires of re-spondents from what we have gathered, above all they want increased institutional support in the form of an online bilingual journal as mentioned above, more inter-national cooperation and interdisciplinary overlaps. It is difficult, however, to decide whether the implementation of these measures would alleviate the feeling of peripherality. On the other hand, we can see the strong points of the potential that respondents are aware of, the ability to follow activities abroad and to communi-cate with foreign art scenes. A provocative question in conclusion might be whether respondents have a sense of being sealed off and a desire for more openness. Certainly it is a subject worthy of closer examination.

BIO:

Zuzana Révészová studied sociology and law at Masaryk University in Brno. Currently she cooperates with tranzit.sk and other cultural and social initiatives in Slovakia and the Czech Republic.